‘Matter in these sighs’: notes on holy breathing

Naya Tsentourou from the University of Exeter writes:

In John Milton’s Paradise Lost prayer is defined as ‘one short sigh of humane breath’ (11.147). Earlier, in a passage that is twice repeated almost verbatim at the end of Book 10, Adam and Eve agree that the humble and appropriate way to pray for forgiveness is ‘with tears / watering the ground, and with their sighs the Air / Frequenting, sent from hearts contrite’ (10.1101-2, and see also 10.1089-1091). Since breath is never purely the physiological act of air leaving or surging into the lungs, its cultural capital is manifest in the performance of religious rites such as prayer. Informed by the etymological and theoretical proximity between breath and soul (see To breathe is all that is required), breath and prayer often emerge as synonyms, rooted in traditions as old and mystical as hesychasm and yoga that conceive of meditation as facilitated and enhanced by controlling the breathing.

The focus of this post is on what I define as ‘holy breathing’: a method of communicating with the divine that relies on breathing sighs and groans to affect God, and to securely denote a subject’s internal state. Drawing my examples from the seventeenth century, I want to briefly sketch a poetics of holy breathing, before I hint at how medical, theological, and literary discourses intersect in the study of devotional sighs and groans.

The poetics of holy breathing

In his ‘Affliction’ poems, George Herbert cites sighs and groans as the symptoms of his intense suffering in the presence of the divine.

My flesh began unto my soul in pain, / Sicknesses cleave my bones; / Consuming agues dwell in ev’ry vein, / And tune my breath to grones.

His affliction is painfully embodied and experienced as penetrating the general and outward ‘flesh’, assaulting the ‘bones’ under it, prevailing in ‘ev’ry vein’, until it is finally expelled from the body in the form of ‘groans’. The ‘tuning’ of breath to groans, apart from depicting Herbert’s lifelong interest in music, highlights groaning as an aural performance that aims to move its audience, as Herbert makes explicit in his poem ‘Sion’: ‘But grones are quick, and full of wings, / and all their motions upward be’. Furthermore, constrained respiration is not necessarily inarticulate: in ‘Affliction (III)’, Herbert writes, ‘my heart did heave, and there came forth, O God!’, signalling the production of breath as a means of addressing God. The petitioner’s role in this process, however, is limited, and regulation of sighing and groaning is not a human task: ‘hadst though not had thy part’, claims Herbert, ‘sure the unruly sigh had broke my heart’. The symptom of suffering, the sigh, not only evades human control, but it turns into a potentially life-threatening experience for the individual, unless God intervenes. Yet, with the speaker’s tone changing from fear to acceptance, condensing life into a sigh is actually welcome: ‘when there’s assigned so much breath to a sigh, what’s then behind?’ Forcefully expelled from the body, sighs carry with them the whole of human existence.

Sighs and groans, therefore, are not only symptoms, but the means of a devotional language that owes much of its psychosomatic vocabulary to the Psalms of David (see for instance Psalm 6). The immediacy, spontaneity, and authenticity inherent in sighing and groaning constitute perfect prayer, as Paul advises in Romans 8.26, a verse widely cited in prayer manuals from the early modern period:

for we know not what we should pray for as we ought: but the Spirit itself maketh intercession for us with groanings which cannot be uttered.

This verse has for centuries influenced interpretations of private prayer as a silent and transcendent practice.

Holy breathing and science

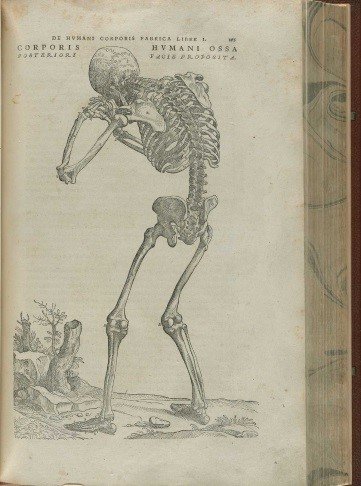

If Herbert’s verse is anything to go by, the poetics of holy breathing rely on an understanding of sighs and groans as physiological processes. Herbert’s attention to flesh, bones, heart, and veins, places devout respiration firmly within the biological body in a period that, prior to William Harvey’s On the Circulation of the Blood (1628), seems to have understood breathing to follow primarily a humoral model. According to this model, respiration was necessary as a cooling agent for the heart, which constantly pumped vital spirits to the rest of the body via the arteries. The pain and suffering that Herbert experiences, or Adam and Eve’s ‘contrite hearts’, might in fact be producing heavy sighs and groans to account for the overwhelming surge of blood to the heart.

Such representation of holy breathing can be further sustained by practitioners of early modern natural philosophy that attempt to explain respiration by resorting to the example of prayer. Thomas Willis, physician and Fellow of the Royal Society, offers such an account in his treatise, De anima brutorum quae homine vitalis ac sensitiva est (1672), on the brain and nervous system:

For truely, almost everybody experiences in himself that in strong Prayer, the Blood is more and more heaped up in the Bosomes of the swelling Heart: wherefore, that the Vacuities of the Lungs might be supplied, we breath deeply, and so the Air being more fully drawn in, the Muscles of the Breast, and the Diaphragma, are detained almost in a continual Systole, or more often iterated; to wit, for this end, that the Vital Blood, to be offered as it were a Sacrifice to God, should be there kept, nor suffer’d to go from thence, or to be inlarged, till as it were by a long immolation, together with Prayers, lieve may be had from the Godhead.[1]

Is this an anatomical representation of prayer or a devotional representation of anatomy? The boundaries are certainly not clear and they needn’t be, as the study of breathing, sighing, and groaning reminds us that the health of individual bodies was (and still is) a medical as much as a theological and literary concern. As Claudius states in Hamlet, ‘there’s matter in these sighs, these profound heaves’ (4.1.1) and that is an essentially multi-disciplinary matter.

[1] An English translation from the Two Discourses Concerning the Soul of Brutes which is that of the Vital and Sensitive of Man (1683) can be found here.