The riddle of breathlessness

Dr. Nabil Jarad, Consultant Respiratory Physician at Bristol Royal Infirmary and School of Clinical Sciences, University of Bristol, writes:

‘I have given up trying to understand the riddle of breathlessness’ exclaimed Professor Duncan Geddes in one of the weekly seminars held at the Brompton Hospital. I was then a junior doctor about to embark on a PhD project in patients with asbestos-related diseases, most of whom were cigarette smokers. That statement from an eminent doctor probably dissuaded me from looking into mechanisms of breathlessness in patients with chronic lung diseases. However, as a respiratory physician, I cannot escape the fact that a large proportion of patients suffer from debilitating breathlessness.

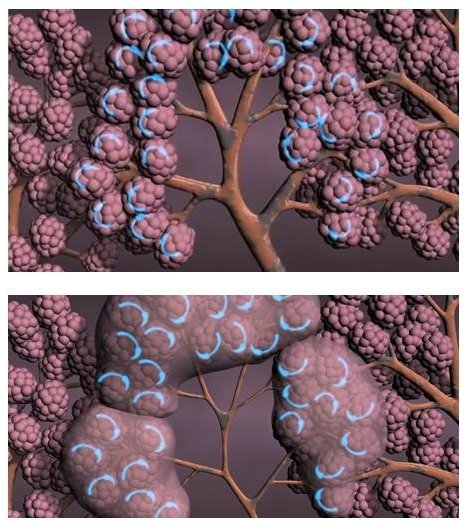

Emphysema is a destructive condition, induced mainly by cigarette smoking. The alveoli (air sacks) are fused together and become inefficient (figure 1).

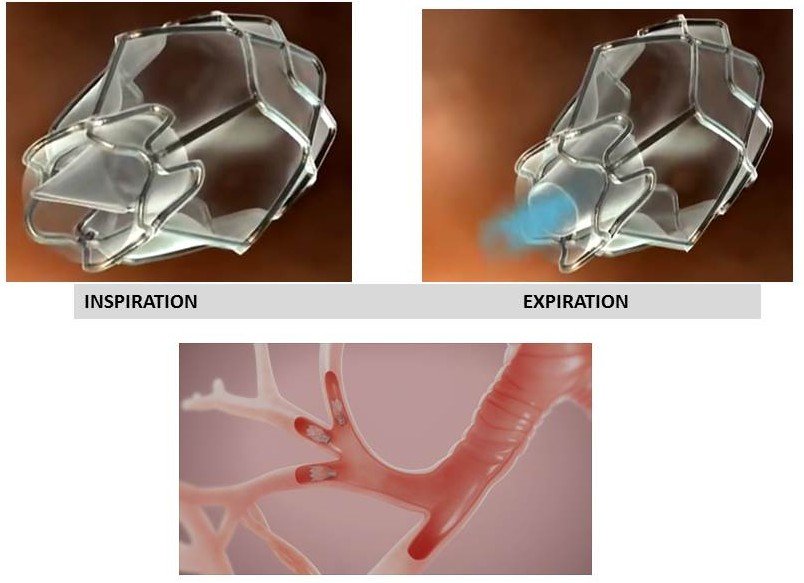

The airways attached to these alveoli are floppy and easily collapsible with every expiration. For those with emphysema, it is easier to breathe in, but very difficult to breathe out. Air trapping and the increase in respiratory effort needed to compensate are probably why breathlessness occurs. A patient with emphysema tries with every breath to stop the airway collapsing by blowing with the lips pursed (figure 2).

Inhalers do not work well in emphysema as the function of the inhalers is to relax the muscle in the airways. This is not a particular problem in emphysema, but might be a problem if medium-sized airways are also narrowed. Many patients with emphysema end up using oxygen therapy.

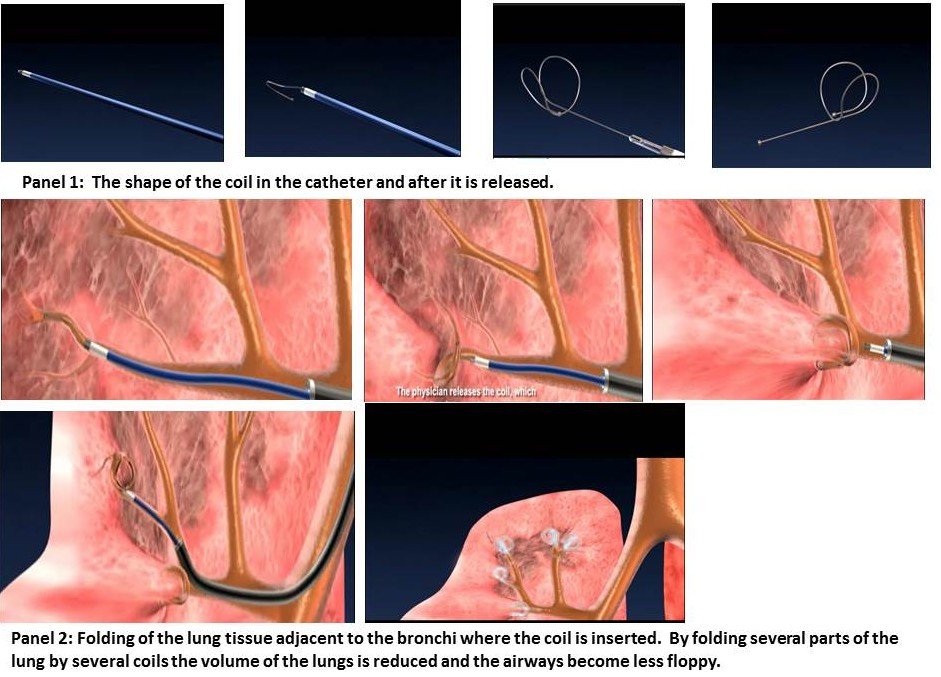

Over the past few years, methods to improve quality of life in those with emphysema have been developed. These methods use devices (valves and coils), trying to achieve two things: firstly, to isolate and collapse the areas of the lungs where emphysema is most localised (this is what one-way valves do, as in figure 3); and secondly to reduce the size of the lungs by folding areas of the emphysematous lungs and decrease the floppiness of the airways (this is what the coils do, as in figure 4).

The procedure of inserting these devices is minimally invasive and done through bronchoscopy and gentle anaesthesia. There are no incisions; the anaesthesia is mild and the patient wakes up few minutes after the end of the procedure. But do they work?

The latest study from the Netherlands found that the majority of patients who were correctly selected and underwent valve insertion achieved good improvement in quality of life measures and in the 6-minute walk tests up to six months from valve insertion.[1] This is associated with improvement in their lung function tests. As for the coils, two studies (one from the UK[2] and the other from Europe[3]) found improvements in breathlessness and 6-minute walks tests six months after coil insertion. These two procedures are, therefore, promising for a selected group of patients with severe disease. However, side effects such as chest infections and coughing up blood are common. For valve insertion, air leak from the lung (pneumothorax) is fairly common (15-20%). The devices are expensive (£5000-£6000 per lung). NICE approved the valves with restrictions, but has not approved the coils so far. The other concern is the absence of long-term data on clinical trials. In order to address that, two large studies are underway to examine the efficacy of these two devices for five years.

It is crucial to point out that valves and coils are not a treatment for everyone. Neither are they replacements of conventional and effective treatment such as smoking cessation, exercises through pulmonary rehabilitation, vaccination against the ’flu virus and proper use of inhalers and oxygen therapy. A careful selection process is needed to choose the best candidates, but at least they seem to offer help to a group of patients for whom previously nothing effective was available.

I am now interested in breathlessness, and I think that I know a little more about it. More significantly, there may be more that can be done to help those with advanced emphysema than before. Professor Geddes may also become more interested. After all, it was his work over fifteen years ago that started the concept of the emphysema valves rolling. This is one of many things he pioneered in his illustrious career as a chest physician.

[1] Kloosters K. et al., American Journal Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2015; 191: A6312