The breath between: art, film, mortality, and AIR

Jenny Chamarette (writer, curator and film scholar and Senior Lecturer in Film Studies at Queen Mary University of London), and Anna Cady (visual artist and curator working within the disciplines of film, film installation, photography and text whose work has been exhibited internationally, including at Tate Modern and Sundance Film Festival) write together:

‘How can you know your body, aside from air?’

The last line of Tami Haaland’s poem, an interpretation of the film AIR, still sends shivers down my spine. AIR is first and foremost a multi-artist collaboration. In it, the moving image artist Anna Cady built a deep and enduring collaboration with another moving image artist working in the South of England, Pauline Thomas (a friend, not just a colleague), whom Anna had already known for some years. At the point when Anna and Pauline began working on AIR together, Pauline had just been diagnosed with multiple myeloma, a cancer of plasma cells in the bone marrow. I have no better way of explaining the emergence of this artistic collaboration than what Anna writes about it herself, and about Pauline:

You were in isolation, about to have your transplant, on that first afternoon, sitting by the window in your room, and I don’t know why, but I was allowed in. You’d bought a kit in order to learn how to do Zen painting while you were stuck in there, and we chatted, and then I asked you to work with me, to make a film about air and you agreed – you didn’t hesitate for a moment.

We got stuck in right there and then. Looking at each other’s films and imagining how we might do the impossible – to make a silent film about an invisible element.

We talked about the breath.

I remember saying, “I’ve got to be honest, I need to say to you Pauline, if we make a film about breath, then for me it will be your breath – and at some point it will be your last breath”.

“Oh that’s fine,” you said breezily as if your last breath was so far away as to be irrelevant to the conversation.

For a year we read, we played and exchanged ideas. Rilke’s Invisible Breath, Proust’s Death of a Grandmother, Wolf’s Death of a Moth, Sebald’s thread of silk stretching from this life to the next, Bachelard’s Air and Dreams… I read out loud to you and their words merged into our thoughts and all the while breath hung in the air and became a part of our film.

I was privileged to watch AIR emerge as an abstract, poetic film – as sketches and imprints, layers of moving image pieces, and gradually as a film in its entirety. In November 2014, as part of the Winchester Short Film Festival, Anna and Pauline installed extracts of films that they had made together and separately in Anna’s home. That weekend, they invited artists, writers (including me) and a dancer to lead and participate in movement and drawing workshops, to reflect on what it means to interpret a work from the body. The layering of this project over the original film, AIR, was what became another project, Embodied Interpretations.

My work with Anna and Pauline, as co-curator of Embodied Interpretations, took me back into the world of poetry. Although I am not a poet, I am often drawn to poetry, for instance in the curatorial project Translation Games that I co-curated with Ricarda Vidal, in which we had invited Anna to participate.

In Embodied Interpretations, Anna invited a series of poets, musicians and sound artists to produce interpretations from the body of AIR – a film without soundtrack. The range of interpretative responses was extraordinary. Many poets, such as Tami Haaland and Briony Bennett, pinpointed the relationship between air and breath, air and mortality, air and the transitory nature of life. Others emphasised air’s life-giving qualities, and the ways that it moves away from language. Air’s chuckles, hiccups and screams became part of a visceral and moving sound poem by a.rawlings and Sachiko Murakami. Others, like Joan McGavin, Steven Fowler and Brian Evans-Jones, drew on associations between light, air, dust and vision in the film, to create quick-witted memories of things half-seen. Sound compositions used micro-sounds, like the striking of a match in Sebastiane Hegarty’s piece, or improvisation to mimic movements across the screen, in Abby Wollston and Tara Stuckey’s cello-clarinet pairing, or Aaron D’Sa and Deepak Venkateshvaran’s piano and tabla collaboration.

The process of selecting, collecting and curating these pieces was painstaking: would the poets or composers mind their work being placed together, or even overlapped? And what effects would these new sounds and words have on the film? Would they overwrite or overrule the meanings that Anna and Pauline had given to it, or even cause discomfort? And how to make these works visible? How to make the complex layering of breath and sound and voice and image visible too?

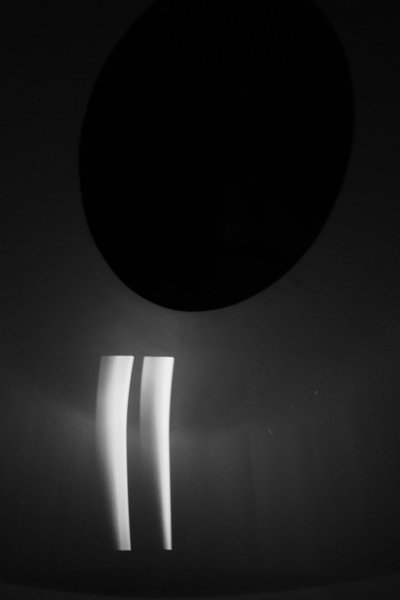

Drawing Breath became the natural title of the two exhibitions that followed, which of course resonates with the Life of Breath’s resident artist’s project. We projected different versions of AIR, with different soundtracks – poems, sound art, musical compositions and improvisations – into two very different spaces. The Manor at Hemingford Grey in Cambridgeshire, is one of the oldest continuously inhabited buildings in the country, situated in a quiet village some miles west of Cambridge, and the former home of the children’s writer Lucy Boston. St John on Bethnal Green, a popular church on a busy crossroads in East London, was designed by Sir John Soane and is a focal point for art and spirituality in the local community. Each site was so very different, each with its own echoes of domesticity or sacredness, age and care, decrepitude and homeliness. At every stage of the project, new ideas came to light. New ways of looking at the film, and looking at the collective collaborations that emerged. Anna went on to install the work outdoors at a magical third site, the James Turrell Skyspace at the Tremenheere Sculpture Garden in Cornwall, in November 2015 (see below).

All the while, Pauline’s illness progressed at intervals that sometimes meant that she was present in full force, joggling projectors and torches up staircases. Sometimes she was present in spirit, kept close to home by serious ill health, and on those times she was much missed. Her work, which was always concerned with mortality, delicacy and transience, leaves heavy traces behind. As part of the Drawing Breath installation at The Manor, and its early incarnation at Anna’s house in Winchester, she made a film of a tiny insect flying through smoke, extinguishing its brief life. The film was played in an equally tiny matchbox. Air is lit and life is extinguished. Blink and you’d miss it. But once you had seen it, it was unmissable.

At the time of the Drawing Breath exhibition at St John on Bethnal Green in May 2015, I wrote that Pauline was living with terminal illness. I wrote it gently, with her permission, because I wanted to point out the ways in which mortality was such a fundamental part of the AIR project, but that it could not, and should not, overwhelm all of the other possible interpretations and creative reflections on air and breath. Again, for want of better words, I am quoting here from my curatorial notes:

Inevitably, there is something elegiac about Drawing Breath. But this is both about Pauline and not about her at one and the same time. It is also about breath as a moment on the precipice between living and not-living, as an invisible trace, as a moth trapped in the lamplight, as a temporary enchantment, as astral dust motes, as smoke unfurling between two towers that coruscate into the dark. As darkness on a bright May evening, as the life of a day lily.

Conversations about AIR, and about the Embodied Interpretations project, have billowed outwards from Pauline and Anna’s original collaboration. The film and its interpretations were part of thoughtful discussions at the Globe Road Poetry Festival in November 2015. AIR won the ‘Best Fine Art Short’ prize at Winchester Short Film Festival 2015. And on 5 March 2016, a version of AIR will be screened at the Whitechapel Gallery in London at an event curated by Sophie Mayer to mark International Women’s Day. The conversations that emerge are not just about air, not just about breath, but also about embodiment, mortality, emotion, connection, creativity and collaboration.

At the time I am writing this blog post for the Life of Breath project, it is a few days after Pauline’s funeral. She passed away on 30 January 2016, peacefully, with her family around her. How she is missed. How she is loved. But the work, AIR, was not consumed by Pauline’s dying breath. AIR was powered by the extraordinary life-giving qualities of artistic creativity, and of the energetic and exciting possibilities that collaboration gives, especially in connection to the air and breath that we share. We are stronger in the multitude than in isolation. The film AIR, and its surrounding exhibitions, Drawing Breath: Embodied Interpretations showed me an energetic space of reflection between life and death. A breath between.

—————————————————-

AIR will be screened at the Whitechapel Gallery in London on Saturday 5 March, as part of a film programme curated by Sophie Mayer to mark International Women’s Day and the launch of her new book, Political Animals: 21st Century Feminist Cinema.

Jenny Chamarette and Anna Cady write together at the talkthinkmake blog.

Pauline Thomas was an award-winning visual artist whose background in painting, an appreciation of Haiku poetry, and the Eastern aesthetic of transparency and formlessness in Japanese ink drawings influenced her approach to filming. Pauline died on 30 January 2016.