Strive and labour more vehemently

by Katie Birkwood, Rare Books & Special Collections Librarian

and Felix Lancashire, Assistant Archivist

Hosting the exhibition Catch Your Breath has been an unexpectedly emotional and thought-provoking experience. As I’ve said several times to tour groups visiting the Royal College of Physicians (RCP), breathing is something that we all do, all the time, and we usually only notice it when something’s going wrong.

For some people that’s a rare occurrence, and for others the struggle to breathe is a constant presence in their lives. The exhibits in the exhibition bring this to life vividly, whether they’re medical, religious, literary, or artistic texts or objects.

One exhibit that I’ve returned to again and again over the last few months is 300-year-old medical book John Floyer’s A treatise of the asthma, published in 1698. Floyer (1649–1734) was a physician who lived in Lichfield. He wrote books on many topics including the properties of medicines, cold-water bathing as a medical treatment, the art of measuring the human pulse, and medical treatment for older people.

His Treatise of the asthma, exhibited in Catch Your Breath, is the first clear published account of asthma and it had a personal importance and significance to Floyer. To use his own words, he ‘suffered under the tyranny of the asthma at least thirty years’.

Floyer’s book gets to the heart of one of the themes of the exhibition: how does, or how can, patients’ own experiences inform the way they’re treated by medical professionals. Floyer notes that having been ‘long subject’ to asthma, he has a better understanding of it than other physicians who rely on second-hand information.

As a fellow asthmatic, the book has a special resonance for me too. I’m lucky in that 21st century medicine keeps my breathing under control most of the time. But Floyer, writing 3 centuries ago, vividly describes the conscious physical effort of breathing when things aren’t going so well:

the Diaphragme seems stiff, and tied … It is not without much difficulty moved downwards, but for enlarging the Breast in Inspiration, the Intercostal Muscles which serve for the raising of the Ribs, and lifting up the Breast, strive and labour more vehemently, and the Scapular and Lumbar Muscles, which serve for strong Inspiration, join all their force, and strain themselves to lift up the Breast and Shoulders, for the enlarging the Cavity of the Breast, that the Lungs may have a place sufficient for their Expansion, and the Air may more plentifully inspire.

John Floyer’s Treatise of the asthma (1698)

This little book is just one of many wonderful objects we’ve been exhibiting during Catch Your Breath. My colleague Felix has been struck by something quite different in the display:

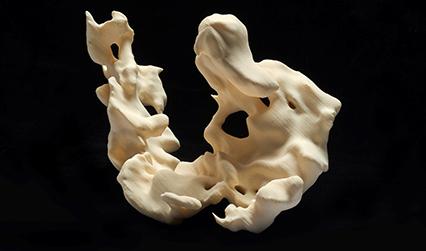

I am fascinated by Jayne Wilton’s sculpture, Concern, a frozen ectoplasmic cloud floating inside a display case, not just because of its captivating appearance, but because of the revelations it offers about breath, breathing and the literal impact that words have on the physical world.

To create the piece, Wilton asked someone to say the word ‘concern’, while she used computer jiggery-pokery to map the air that was displaced as they spoke, and then create a physical 3D model of the air.

The piece, which is about the size of a barrister’s wig, perfectly demonstrates one of the messages of the exhibition, that breath matters (indeed, is matter!), breathing is a physical interaction with the air around us. If this is what we’re breathing out, what are we breathing in? But I’m also thrilled by the fact that this is a model of a spoken word, that words have a real shape beyond their written representations. As a comics fan, I’m used to characters’ speech floating in balloons next to their heads; well, here is an actual word balloon! We know language is powerful, but here is the proof that our words are actual physical objects, balloons of meaning that we’re responsible for sending out into the world, and we’re responsible when they explode.

Felix Lancashire

Courtesy of Jayne Wilton

At the end of the week, Catch Your Breath will close its doors at the RCP, and move to a new venue at Southmead Hospital, Bristol from 24 September 2019. We hope it will continue to inspire people to think more deeply about the meaning of breath.