Portrait Therapy for Life Support?

Susan M D Carr, art therapist at the Prospect Hospice and PhD Student at Loughborough University, writes:

I was in a CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation) training session the other day, about to assist a ‘collapsed person’ in the form of a Resusci Annie, when the instructor asked, “What is the first thing we should do?” Immediately my hand shot up.

“Take their pulse?” I said.

“No!” the instructor said. “No time – first check if they are breathing! If not, then begin the CPR protocol.”

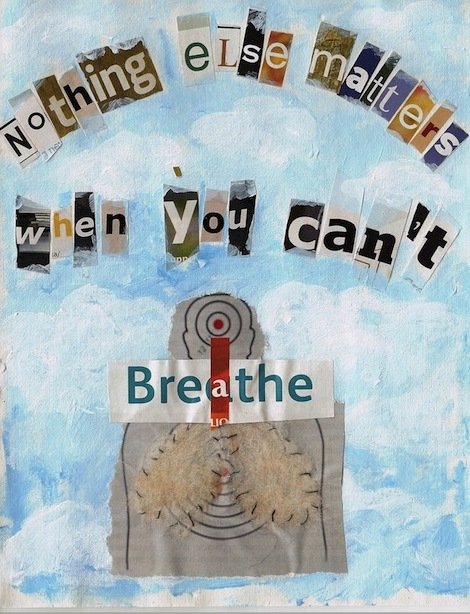

This reminded me of something a participant/collaborator called Peter once said to me whilst working together on my PhD project developing an intervention called Portrait Therapy (Carr 2014). Peter, who was living with COPD had said, “you have to remember that … nothing else matters when you can’t breathe”. I even made a collage of this as a form of response art for Peter (see figure 1), and yet in that moment in the CPR training I had forgotten the fundamental life-sustaining nature of breathing.

Figure 1. Nothing Else Matters, collage by Susan Carr, 2011

Before his COPD became severe, Peter had been an active member of the Breathe Easy support groups run by the British Lung Foundation, helping others to face their diagnosis with dignity and hope, giving talks to many different organisations explaining what it is like to live with breathlessness. When we first began working together on the Portrait Therapy project, Peter was no longer able to take this active role. He had also been recently bereaved, his son Mark having died of cancer six months previously.

The psychological and emotional impact of bereavement is well documented (Parkes & Prigerson 2010), but the physical impact is often less considered. Therese Rando (1991) talks of a lady, who was both a bereaved parent and a widow, who said, “When you lose your spouse, it is like losing a limb; when you lose your child it is like losing a lung.” This seems to indicate that Peter had suffered a double blow where his breathing was concerned, living with both COPD and the recent loss of his son.

In my work as an art therapist at the Prospect Hospice in Swindon, I have noticed that people living with life-threatening or chronic illnesses often describe the impact of their diagnosis, treatment and illness as having changed their sense of self-identity, characterised by saying “I don’t know who I am anymore”. I developed Portrait Therapy as an intervention to help people find ‘health within illness’ (Carel 2008) by developing a stronger, more coherent sense of self-identity when facing these losses. One of the common themes to come out of the project was the way participants used the portraits to mourn their losses and bring a sense of ‘closure’ to previous bereavements.

In Judith Butler’s (2004) book about the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Centre in New York, she examines the nature of mourning. We need to mourn, Butler suggests, as a way to acknowledge our ‘ontological indebtedness’ to each other. As she says:

It is not as if an ‘I’ exists independently over here and then simply loses a ‘you’ over there, especially if the attachment to ‘you’ is part of what composes who ‘I’ am. If I lose you, under these conditions, then I not only mourn the loss, but I become inscrutable to myself. Who am ‘I’ without you? (Butler 2004: 22).

This may begin to explain the relationship that people living with chronic illnesses have with lost aspects of their identity, meaning that the question ‘who am I without you?’ becomes intensely intrasubjective, and without mourning these losses people become ‘inscrutable’ to themselves.

Focusing on the loss of Peter’s father of Mark self-identity, we co-designed (and I painted) six portraits of Peter and Mark, including a portrait of the two of them together (see figure 2).

Figure 2. At the Races by Susan Carr (co-designed by Peter)

Our weekly Portrait Therapy sessions became an important focus for Peter and in an interview at the end of the project Peter said that the project had helped him “accept the loss of Mark”, saying “now I can talk about him without crying”. Through designing the portraits and collages, Peter was able to acknowledge the stories and events from his life which shaped his self-identity, both those that have made and un-made him.

As Joy Berger says, art and creative expression ‘can empower us at life’s most challenging moments. It can voice one’s darkest struggles. … Oppression can become vision. Despair can become determination’ (Berger 2006: 111). Ultimately Portrait Therapy helps those living with illness to take time to rediscover their sense of self-identity through co-designing portraits that reveal how they wish to be portrayed, physically and spiritually. As John Updike once said, “What art offers is space – a certain breathing room for the spirit.”

References

Berger, Joy S. (2006) Music of the Soul: Composing Life out of Loss. Routledge Publishing Ltd, Abingdon & New York.

Butler, Judith (2004) Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence. Verso: London & New York.

Carel, Havi. (2008) Illness: The Cry of the Flesh. Acumen Publishing Ltd, Stocksfield UK.

Carr, Susan M.D. (2014) ‘Revisioning Self-Identity: The role of portraits, neuroscience and the art therapist’s ‘third hand’. The International Journal of Art Therapy, Vol. 19, Issue 2, pp. 54-70, 2nd July 2014.

Parkes, Colin Murray & Prigerson, Holly G. (2010) Bereavement: Studies in Grief in Adult Life. Routledge Publishing Ltd, Hove & New York.

Rando, Therese A. (1991) Parental adjustment to the loss of a child, in Papadatou & Papadatos (eds) (1991) Children & Death. London: Hemisphere Publishing Corporation.